“What’s in a word?”

ALBUM

Pronunciation: \’al-bəm\

Function: _noun

Etymology: Latin, a white tablet, from neuter of albus

Date: 1612

1a: a book with blank pages used for making a collection (as of autographs, stamps, or photographs) b : a cardboard container for a phonograph record : jacket c : one or more recordings (as on tape or disc) produced as a single unit

2: a collection usually in book form of literary selections, musical compositions, or pictures : anthology

TRACK

Pronunciation: \’trak\

Function: noun

Etymology: Middle English

trak, from Middle French trac

Date: 15th century

1a: detectable evidence (as the wake of a ship, a line of footprints, or a wheel rut) that something has passed b : a path made by or as if by repeated footfalls : trail c : a course laid out especially for racing d : the parallel rails of a railroad e (1) : one of a series of parallel or concentric paths along which material (as music or information) is recorded (as on a phonograph record or magnetic tape) (2) : a group of grooves on a phonograph record containing recorded sound (3) : material recorded especially on or as if on a track f : a usually metal way (as a groove) serving as a guide (as for a movable lighting fixture)

2: a footprint whether recent or fossil

3a: the course along which something moves or progresses b : a way of life, conduct, or action c : one of several curricula of study to which students are assigned according to their needs or levels of ability d : the projection on the earth's surface of the path along which something (as a missile or an airplane) has flown

4a: a sequence of events : a train of ideas : succession b : an awareness of a fact, progression, or condition

5a: the width of a wheeled vehicle from wheel to wheel and usually from the outside of the rims b : the tread of an automobile tire c : either of two endless belts on which a track laying vehicle travels

6: track-and-field sports; especially : those performed on a running track synonyms see trace

track·less `trak-ləs\ adjective

in one's tracks : where one stands or is at the moment : on the spot

on track : achieving or doing what is necessary or expected

kunstaspekte: Could you make a statement on the concept of your K21 exhibition ALBUM/TRACKS A and its architecture, which you have developed in close collaboration with the Belgian architect Kris Kimpe?

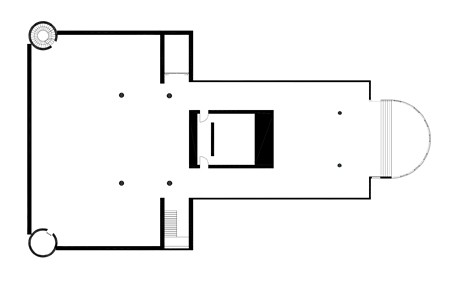

Ana Torfs: The space for temporary exhibitions at K21 is located in the basement. This basement is one huge open space – except for a black box in the middle of it – with impressive walls reaching 5.5m high. The Ständehaus, a former parliament building, in which K21 opened its doors in April 2002 after a drastic redesign, dates from the end of the nineteenth-century. When taking a look at the current floor plan of the basement, one immediately notices the neo-classical, symmetrical structure of the original building, including a semi-circular space, known in K21 as the apsis. (Plate 01)

Until now, for each temporary exhibition in the basement of K21, new spaces have been made to measure, adapted to the works of artists as diverse as Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Lawrence Weiner or Wilhelm Sasnal. The technical director of K21, Bernd Schliephake, has invented a reusable prefab system, consisting of movable metal structures covered with plywood. These freestanding walls have a standard thickness of 45cm – a very conclusive aspect which is important to take into account when working on the architecture of a show at this location.

At the end of 2008, Kris Kimpe, a close friend, suggested that he would be happy to think with me about the floor plan of my solo exhibition ALBUM/TRACKS A. Early in 2009, I showed him my drafts and we discussed some of the core ideas I had in mind for the exhibition architecture: long, empty corridors which creates distance (and time) between the works, no use of colors in the entire basement, typography showing the titles of each work on the white walls of these corridors, entries to each space reaching to the ceiling etc. I also told Kris that I did not want to use the existing black box in the middle of the basement, but would close it off instead and use the area around it as a central seating area. I also wanted the apsis to be part of the space, though it was excluded in most of the temporary exhibitions I saw in K21 until now. It’s the only room in the basement where daylight enters through the circular windows and where one can see the external world, which makes this room very special. Finally, I did not want to make a fixed exhibition circuit, but give every visitor the freedom to create his own trajectory.

I would like to stress the fact that there is not something like the architecture of ALBUM/TRACKS A, and the works, as if these were two separate entities. I don’t believe that one can create exhibition architecture first and then put works in that architecture. I think it only makes sense to work with an architect on a solo exhibition if there is the possibility of a continuous dialogue with the artist. The architecture should develop from the works and their particular needs and not the other way around. At the same time, I also think it is important to take into account the existing architecture of the place where one will exhibit.

The most difficult thing for me to do was to decide which works I would show at K21 and which ones at the Generali Foundation. ALBUM/TRACKS B, the second part of the exhibition, opens in Vienna on September 3. The venues have a different scale and each has its very distinct architecture – even the empty basement of K21 has very specific characteristics. For every exhibition one has to start from zero again, taking into account the typical features of the venue in question. As a result, ALBUM/TRACKS A at K21 and ALBUM/TRACKS B at the Generali Foundation will look very distinct. The two shows, with a partly different selection of works, complement one another and offer a complete overview of my work to the present day, including three new works.

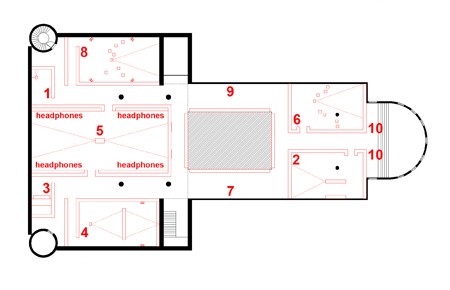

The ten works I selected for K21, covering a period of seventeen years, are very diverse. Some installations need to be shown in relative darkness, like Battle and The Intruder, while others such as the photographic series Vérité exposée, Family Plot #1, Legend and “à…à…aaah!” need artificial lighting. Consequently it was obvious that Kris and I needed to create compartments in the open basement space, so that each work could be presented in an optimal way. At the same time, I didn’t want to lock the works up in hermetically sealed black boxes. Though the exhibition space is divided into several rooms, these are rather light and open, thanks to the large, high entries to each white space.

In this context it’s also important to mention that most of the (slide) installations exhibited in ALBUM/TRACKS A have been shown already on several occasions in solo and group shows. I have a quite precise idea of how to exhibit each of them. These installations have many architectural (spatial) characteristics of their own. It’s more than just a projection of a slide on a wall, as I will try to explain later.

kunstaspekte: The arrangement and symmetry of the impressive structured space makes me think of the ground floor of a church (something like an archetypus), with its nave, aisle chapels and apse.

Ana Torfs: A church was the last thing on our mind when working on ALBUM/TRACKS A! When taking a closer look at the floor plan of my exhibition, one perceives a somehow symmetrical structure which echoes the symmetry of the original nineteenth-century building – but when experiencing the space it does not feel symmetric at all. Every work is installed in a completely different way, and that also distorts the perception of the symmetry. (Pl.02)

I guess that the personal reference frame of each visitor will give way to very diverse connotations or associations when walking through the exhibition. Several visitors have actually perceived the exhibition as a labyrinth, the complete opposite of symmetry! Others have referred to a city map: this allusion makes perfect sense as there are dark and light alleys to follow, large and small roads, tracks that lead nowhere as well (but to the emergency exits), a bright square with benches to sit and rest etc.. It reminds other people of an archaeological excavation ground, not exactly an example of symmetry either. A Belgian visitor even found it very meaningful that I was exhibiting in a basement, as he described my work, in the literary magazine nY, as Grundlagenforschung, fundamental research by the means of art.

“What’s in a word” – a linguistic interest that is one of the recurrent starting points in all my works – is also reflected in a subtle way in the exhibition architecture. It’s no coincidence that I started this conversation with the etymology of the two words that I chose more than two years ago for the title of the exhibition and of the closely connected catalog ALBUM/TRACKS A + B, in which these words and their etymology figure in white ink on the black endpapers.

The word ALBUM interested me because of its connection to the word “white” (albus):  the white walls as a metaphor for the unwritten, empty page, for the white projection surface. But I was also interested – as this is my first big overview exhibition – in the actual meaning of the word album as “anthology”.

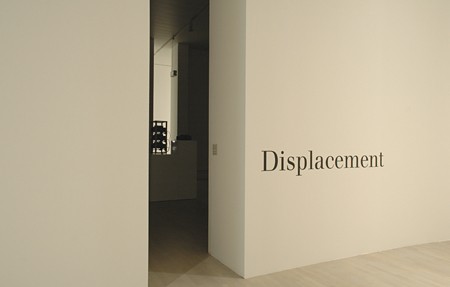

The second word, TRACK, used in plural, with its manifold meanings, completed the title. The long “roads” between/leading to the works could be referred to as tracks to follow for example. (Pl.03, Pl.04, Pl.05, Pl.06, Pl.07, Pl.08)

kunstaspekte: The clear-cut spatial arrangement of the whole exhibition space in K21 defines the construction of your slide installations as well, up to the very last details.

A. T.: But I don’t think the architecture of the exhibition space defines the way my installations look, it’s rather the other way round, as I mentioned already.

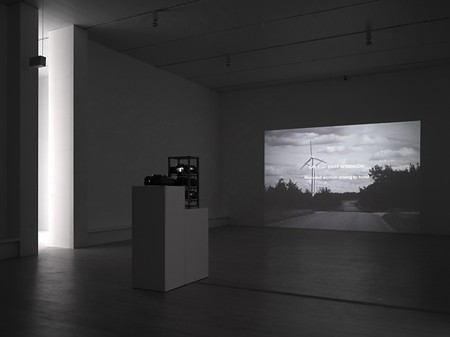

In the case of Displacement, for example, a new work shown for the first time in Düsseldorf, I organized a private preview in Wiels, Brussels, in March 2009, to find out the ideal dimensions of the space and the projection size of the images. I didn’t want to take the risk to build a space for Displacement in an exhibition without having “tested” in advance the type of space necessary for the work in question.

This ideal space turned out to be rather large (20 x 10 meters), but the two socles that were placed in the middle of the space divide it visually in two. As the two projections take place on opposing walls, you can’t see both images at the same time and you perceive the space smaller than it actually is. The projected images are 5.5 meters large. This seems big, but it works very well for Displacement. In some of my installations, though I work with slide photography in the first place, there is evidently a relation to cinema – I especially like the big projection size of the cinematic image. I also prefer to project the images directly on the walls of the space – not on special screens – so that the image becomes part of the architecture.

In this case, as for all the works in the exhibition at K21, it was the work that was the starting point for the architecture needed, as you can clearly see on these installation views made during the preview in Brussels. (Pl.09, Pl.10)

As long as I didn’t know the dimensions of the space necessary for Displacement it was not possible to make a final selection of the works for the K21 exhibition. As mentioned earlier I wanted to create a lot of space between the works and without exact knowledge of the minimal dimensions needed for optimal presentation of each work, I was stuck.

The day after the preview, I wrote Kris Kimpe with the dimensions needed for Displacement, after which we could finalize a first draft of the floor plan. On seeing the big space of 20 x 10 meters for Displacement on the plan, in the middle of the left wing of the building, separated from Battle and The Intruder by two long corridors, it was clear that we should draw two entrances to the space, which we decided to place asymmetrically. (Pl.11, Pl.12)

Kris suggested that we give both entrances recessed walls of 90cm deep (2 x 45cm, the size of the prefab system used in K21). It’s a very interesting architectural detail: It creates a movement and invites the visitor to enter the space. The movement from “outside” to “inside” almost follows the pattern of a slow fade from light to black. The boundaries between inside and outside become blurred. At the same time these gates, which were also built in the spaces of Anatomy and Du mentir-faux filter the bright spotlight from the surrounding corridors. (Pl.13)

During the preview in Wiels, I also discovered that most of the members of the small audience I had invited moved the stools put at their disposal against the longest walls of the space. This led to the decision to install benches instead of stools in the “Displacement” room at K21. The hollow space that was formed between the prefab wall of 45cm thickness and the recessed walls of the two entrances turned out to be ideal to install long benches of 45cm deep and 45cm high, as if they were part of the space. They also turned out to be the perfect furniture to put the wireless headphones with the audio narration on. (Pl.14)

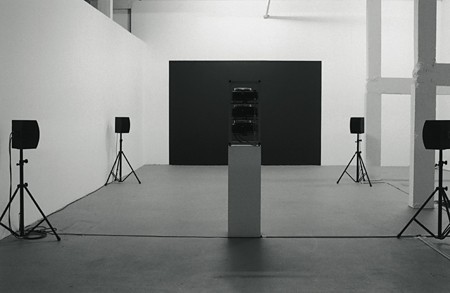

In general I prefer exhibition spaces that are open and intimate at the same time. I like the idea that you can really focus on a work, but I also don’t want the visitors to feel locked in soundproof dark rooms. Even though the plywood walls are 45cm thick, the voices of “Battle” and “The Intruder” are still audible throughout the exhibition, but it is not disturbing at all, on the contrary. The constant murmur, like the high entrances, creates a kind of transitional space between the works, which can make the visitors curious to discover them. The darkest space in the exhibition is that of The Intruder, but that is inherent to the work as well, which is based on a play by Maurice Maeterlinck, focusing on the senses of hearing and seeing. The images are projected on a black projection surface, which absorbs most of the light of the projectors: a radical and very suggestive conceptual choice, a metaphor for the blindness of the principal character. It could also be seen as a playful reference to ‘day for night’. ‘Day for night’, also known as ‘nuit américaine’ (American night), is the name of a cinematographic technique to simulate a night scene. The ‘filtered’ slide images that appear on the black projection surface are also reminiscent of early photography and daguerreotypes, with different hues in the range of brown and bronze tones.

The four loudspeakers are placed such as to form an auditive square around the socle. (Pl.15, Pl.16)

Once again the visitors have the possibility to feel immersed in the large projected images. The life size figures in the images are mirrored with the visitors in the space.

kunstaspekte: Most of the time the axis of projection runs across the longest axis of the exhibition space.

Ana Torfs: At K21 the slides are indeed projected across the longest axis of the space, but this is not always the case, and it’s certainly not a fixed practice. The reason is technical in the first place… Let’s take Du mentir-faux for example: In 2007, I presented this slide installation in a group exhibition at the Fotomuseum in Winterthur, in an interesting space, full of pillars. The minimum depth I need to install Du mentir-faux is 7 to 8 meters. Most museum and gallery rooms measure +/- 5 by 11 meters, which explains why in most cases I’m obliged to project across the longest axis of the space… In Winterthur the shortest axis was more than 7 meters, so in this case it was technically possible to project the images on the longest wall, across the shortest axis of the space. (Pl.17, Pl.18)

When I exhibited Anatomy, in 2007, at Argos, centre for art and media, Brussels, a huge dark space with red brick walls, I decided to have a 15 meters long white wall built, 3 meters high, which traversed the space diagonally. On one side of the wall I presented Vérité exposée, in two rows of twelve prints each. The visitors of the exhibition could follow the track created by the strip of neon light on the floor to enter the other, darker side of the long space that was divided by the long wall construction where Anatomy was installed. Once more a very different situation, where a new axis was created within the existing space. (Pl.19, Pl.20)

kunstaspekte: Frontality and a few fixed viewing angles seem to determine most of the installations. What is the idea of focusing the spectator on a fixed point of view and fixed horizons?

Ana Torfs: Frontality is a convention when you work with projected images. Technically you can look at the images in the most optimal way where you’re standing or sitting in front of them. But the same goes for photographs, paintings and all two-dimensional media. All the same I try to add a three-dimensional aspect to my installations. I don’t create black boxes with horizontal rows of seating furniture, imitating a movie theatre. On the contrary: I prefer spaces in which the visitors can circulate freely. I also work with loops, in which the visitor can enter or leave at any point. The visitors don’t need to sit, and if they wish to, the seating furniture gives them the option of various viewing angles. Especially in Anatomy, but also in Displacement there are various possibilities of perceiving the work. You actually have to “move” your ears and eyes to get access to the many layers of these works.

In Anatomy the visitor can sit on the bench and just look at the two television monitors, but he can also switch viewing points completely, by either looking at the monitors or at the huge slide projections on the wall, left of the monitors. The visitor can also choose to stand next to the three-meter long socle and listen with headphones to the English translation, by a court interpreter, of the German testimonies, but he can connect this sound as well to the slowly changing slide projections, without even looking at the young actors on the video monitors.

If there is frontality in my installations, I think it’s present within the images themselves. (Pl.21, Pl.22)

kunstaspekte: In Displacement, slides are projected on opposing walls, from two socles in the middle of the space. In Battle, a slide projector and a video beamer project on adjacent sides of a wall in the middle of the space. In Approximations/Contradictions the visitor, who needs to use computer and mouse, is immediately involved and focused within the symmetry of the installation (bench, table, computer, projection). What is the significance of this axial relation and its strict symmetry, which includes the viewer by means of adjustment and positioning of the projectors and benches?

Ana Torfs: As a matter of fact, the small space for Approximations/Contradictions is the only work in the show with strict and fixed viewing conditions. It doesn’t make much sense walking around here, as you need to navigate with the mouse and the computer.

Approximations/Contradictions was commissioned by Dia Art Foundation, New York, in their ongoing series of web art projects, and anyone with an Internet connection can look at it (and has been able to since December 2004) on www.diaart.org/torfs. I hesitated to include this work in the exhibition, but it was the wish of curator Doris Krystof to show it. I like this work – based on music composed by Hanns Eisler, on texts of Bertolt Brecht´s – very much and it’s fascinating for museum visitors to discover it. Being interested in responding to the setting in which people typically view the web (alone in front of a computer), I wanted to offer a kind of intimate cinema. But when showing this work in the public space of the museum, the scale and conditions are very different from a private viewing situation at home. By adding a video projector, the intimate becomes more public, which creates an interesting tension. (Pl.23) ;

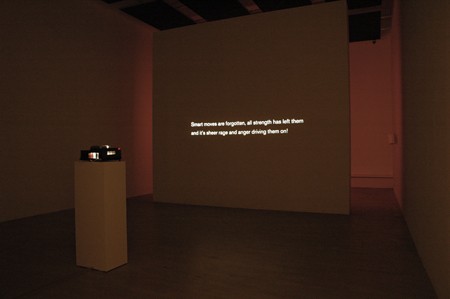

For Battle, a work based on a scenic madrigal of Claudio Monteverdi´s (with a libretto by Torquato Tasso), the spatial arrangement is part of the work too: I often concentrate on the relation or tension between text and image, between what you see/hear and what you read. When entering the Battle space, the first thing the visitor perceives is text slides projected on a freestanding wall, which is part of the work, in the centre of the space. You can move freely in this antechamber and read the shifting text slides, which confronts us with a deadly fight. If you look carefully you perceive that the text slides change to the rhythm of music coming from the other part of the room. After a few minutes the visitor will be drawn to the red light, visible in the back of the room, where you can discover the video projection, on the other side of that same freestanding wall. When you look at the floor plan this space looks more or less symmetrical, but again, when you move around in the Battle space you don’t perceive this symmetry at all. (Pl.24, Pl.25)

We’ve already discussed the architectural details of the work Displacement, but I’d like to add a few more remarks on it to end with. In Displacement the frontal close-ups of a man and a woman are projected on one side of the space, in very slow fades from black to bright light and back to black. On the other side, right in front of the images of the man and the woman, we see a kind of travel story evolve. Couldn’t we perceive the images of the man and the woman as a kind of extension of the slide projectors, more or less as the “mental projectors” of the whole travelogue? In the catalogue ALBUM/TRACKS A+B, published on the occasion of the exhibitions in Düsseldorf and Vienna, Kassandra Nakas describes it as follows: “The travel motifs are juxtaposed with huge close-ups of a man and a woman. Although immediately identifiable as the ‘damaged’ couple in the story, they are also simultaneously the viewers’ opposites and doubles, looking them in the eye and seeing what they see. The act of viewing, of seeing as perception, thus becomes an important component of the installation.” The two asymmetrically placed entries, together with the changing light caused by the slow fades of the man and the woman, distort the symmetry of the room and change the perception of the overall space the whole time, as if it were a kind of evolving light sculpture.

More info about the works: ALBUM/TRACKS A+B, Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, with texts by Mieke Bal, Sabine Folie, Anselm Franke, Michael Glasmeier, Steven Jacobs, Doris Krystof, Friedrich Meschede, Kassandra Nakas, and Catherine Robberechts. The book also contains a long email conversation between Gabriele Mackert and the artist. 204 pp.

*

Ausstellung Ana Torfs, ALBUM/TRACKS A im K21, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 27. Februar - 18. Juli 2010